Permeability and Legibility of the Layout

A street layout that encourages walking and cycling is permeable in that it is well-connected and offers a choice of direct routes to all destinations. It is also legible, in that it is structured to provide a comprehensible distribution of distinctive places and spaces; this allows easy, effective orientation and navigation, and is particularly important for the partially sighted, the blind and people with dementia, for whom clear wayfinding plays a part in encouraging interaction and reducing isolation.

The Street System

A residential area should be structured around a street system made up of urban spaces, and such spaces should be formed according to the principles of this guide.

Design of the street system should start with the establishment of a clear and legible articulating structure for the area. It is important not to allow design to be dominated by the technical demands of traffic, the fundamentals of which are likely to alter significantly as technology evolves to incorporate autonomous and semi-autonomous vehicles. The overarching layout may instead be suggested by topography, natural desire lines and/or access points to the site.

In the words of the Belfast Healthy Cities report ‘Walkability Assessment for Healthy Ageing’, the street system should be ‘designed around pedestrian use or cycleways after its form has been established by urban design criteria, with particular attention given to ensuring accessibility of the layout to the elderly or disabled.’

Permeability

It should be possible for pedestrians and cyclists to move freely between all parts of a layout, both locally and on a wider scale. The disadvantage of a layout based entirely on culs-de-sac and loops is that routes for pedestrians are indirect and boring; pedestrian and cycle movement is thereby discouraged in favour of car use. This creates dead areas which are vulnerable to property-related crime. Cul-de-sac layouts also result in higher traffic levels on feeder roads, and consequently have a negative impact on residents of those roads.

The use of such layouts can also deter the elderly, less mobile or those with dementia from engaging with the wider community. The design lends itself to walking long distances to access services and facilities, which is unattractive to both the elderly and the less mobile, while the presence of dead ends can cause confusion and anxiety for those with dementia. In addition, the repetitive nature of these layouts, with no clear distinction between areas, can add to a sense of confusion.

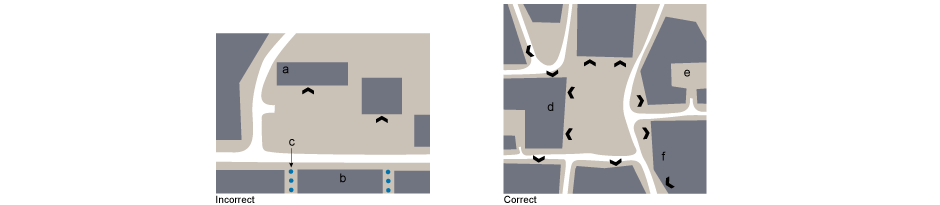

a. Pedestrian/cycle street linking parts of road network

b. Crossroads possible where one branch serves few dwellings

c. Indirect pedestrian route and lack of route choice

d. Heavier traffic loads

a. Pedestrian/cycle street linking parts of road network

b. Crossroads possible where one branch serves few dwellings

c. Nodal point

d. Frontage to major road reserved by private drives

e. Pedestrian/cycle link across major road

f. Ransom strip prohibits vehicle access

g. Pedestrian/cycle link between new and existing

A more permeable layout offers pedestrians and cyclists a choice of routes, thereby providing greater visual interest and generating a higher level of pedestrian and cycling activity. This in turn enhances the security of those using the routes.

The higher the number of pedestrians on the street, the greater the chance of casual social encounters and the lower the chance of thieves gaining access to houses or cars unobserved. This is a benefit to all age groups and to people with a wide range of physical and mental abilities. Higher numbers of pedestrians also help to reduce the risk of social isolation among the elderly, the less mobile and people with dementia.

From a freedom-of-movement perspective, the development ideal is a deformed grid based on the small residential block. The advantages of culs-de-sac and loops in preserving amenity and quiet, supervised space can be combined with those of a permeable layout by bringing the heads of culs-de-sac together, or else by creating pedestrian/cycle streets between otherwise separate parts of the road system. Pedestrian and cycle links can also be created across major roads that would otherwise form a barrier.

There is evidence to suggest that more permeable layouts have a positive impact on local economies both through direct income (trade) and fiscal savings. The Living Streets report ‘The Pedestrian Pound’ (2013) noted up to 40% increases in trade when places are made attractive to pedestrians. Work commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in 2011 assessed the economic impact of improving walking and cycling infrastructure; it found that the costs of the improved infrastructure were significantly outweighed by the savings to local healthcare services – at a ratio of 60:1 for walking and 168:1 for cycling. A number of tools (including the Heath Economic Assessment Tool, or HEAT) have been developed to provide quantitative evidence for such claims, and their use should be considered during the development process.

Wherever possible, a permeable layout should offer both good connections between adjacent housing schemes and where applicable the wider locality beyond the developments, including a choice of routes between one location and another. Where it is not viable for traffic routes to link existing and new residential areas, whether because of ‘ransom strips’ left by developers or because of the need to avoid introducing new traffic into existing residential developments, pedestrian and cycle links between the relevant areas may offer a solution, providing the links are overlooked. It should be remembered, however, that permeability should not be pursued to the detriment or exclusion of other goals – most particularly the need to focus a layout on cores and nodal points.

(Left) Incorrect. Conventional neighbourhood centre

(Right) Correct. A neighbourhood core centre

a. Buildings isolated within layout

b. Residential area segregated from community facilities

c. Pedestrian access across major road and car park

d. Buildings directly front streets, with a high concentration of entrances

e. Car parks fragmented and located at rear of buildings

f. Residential buildings form continuous frontage with community facilities

Page updated: 29/07/2019